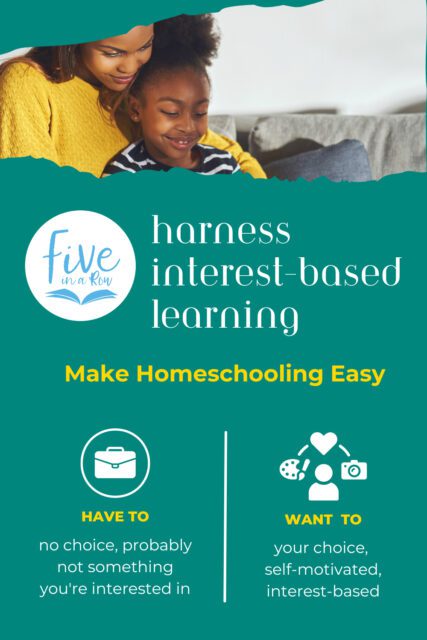

Why we learn new things often determines how we learn them. As adults, there are two options when it comes to learning new things:

Have to: no choice, probably not something you’re interested in

Want to: your choice, self-motivated, interest-based

When a job or school drives learning (have to: no choice, not something you’re interested in), it often results in learning the material however it is presented to you—books, classes, lectures, tests, etc… How we learn something can be enjoyable, easy, a struggle, impossible or somewhere in between. Often, learning is more challenging for us when we don’t have a choice in how we are learning. Reading a book isn’t always a great fit for every learning style, the same is true for listening to a lecture, or taking tests. Learning through methods that don’t fit your learning style can make recalling and retaining information more difficult.

If you want to learn something (your choice, interest-based, self-motivated), you will find resources for yourself to learn from. Consciously or subconsciously, you will likely research and find resources that present the material you want to learn in a format that you learn from the best. If you remember what you hear, you might find a podcast or audiobook—whereas, if you remember what you see, you’d likely find videos or photo tutorials—if you remember what you do, you might find an in-person class or tutor to learn from in a hands-on way.

Guess what? Kids learn in the same way as adults!

When we can teach children using interest-based learning, we teach them to become self-motivated to find answers to their own questions—they will enjoy learning and retain more of what they learn. If we can find ways to present learning material to children in a format that matches their preferred learning style, we increase their retention.

Here’s a question that greatly determines the how and the why of the learning that will happen in your homeschool. “Do I have to teach kids everything in the order it is presented in the textbooks for K-12?”

Certain subjects must be taught sequentially—math, reading (phonics), spelling, and grammar. In these subjects, things build upon previous learning. You have to learn how to count and add before you can replace a number with a letter in algebra and work the equation. You have to learn your letters before learning to read or write.

In high school, I read a book called The Pinball Effect: How Renaissance Water Gardens Made The Carburetor Possible – and Other Journeys Through Knowledge by James Burke. This book had fascinating stories and facts and, unlike most books, was designed to be read interactively by incorporating cross-chapter references that took you from one item to something completely different but influenced by the first. It taught me that people, places, different historical periods, and inventions are interconnected.

Do we have to teach things in a scope and sequence—in the order they appear in textbooks or as they are taught in public school? Does it matter if I learn geographically where Greece is first, or if I learn about the Olympic Games before or after I learn about Curling (the broom-sweeping ice sport), or if the Olympic Games were originally held in Greece at the sacred site of Olympia? The order in which I learn these facts does not matter. I don’t have to learn about Ancient Greece and the start of the Olympic Games to enjoy and learn about Curling (an Olympic sport) or the geography of Greece. If I learn these facts twenty minutes or twenty years apart, they still build upon one another in an interconnected way without relying on each other to enjoy or learn about any other part.

If your child is fascinated with insects but your science curriculum has a section on rocks next … is it more productive to your child’s education to set the curriculum aside and learn about insects or to have your child wait until insects come up in the textbook later in the year or the following year? Which option harnesses the power of “want to” or interest-based learning? Does it matter if your child learns about insects in second grade versus 3rd grade? Asking yourself these questions or ones like these can often help guide you in finding answers that will help you teach your child in a way that increases their interest and retention.

Working through a traditional textbook certainly isn’t wrong; some adults and children enjoy knowing what comes next and sticking to it. Five in a Row provides the best of both worlds for teachers and students by providing a teacher’s manual with lessons laid out for you that are interest-based for your student. Each Five in a Row lesson is tied to a wonderful story you are reading together that week–this creates interest in a lesson that might not normally interest your student. For instance, learning about the human body and the appendix might not be at the top of your student’s interests…but after reading Madeline and hearing about how she had surgery to remove her appendix, suddenly, there’s a connection that creates an interest within your student.

Do not be afraid of going down a rabbit hole. Often, these are the best days of learning for you and your student. “Going down a rabbit hole” is when you are reading a book or studying a subject and you or your student take a particular interest in something you’ve just read that is not what you are currently learning about or on the day’s lesson plan.

As I typed going down a rabbit hole, it reminded me of Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. After looking it up, I learned that Alice in Wonderland is the “common name,” while the true title is Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Also, Lewis Carroll was a pen name for the author, whose real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. A pen name, also known as a nom de plume (just “pen name” in French), is a pseudonym that is defined as a fictitious name, especially one used by an author.

I’ve just taken you down several rabbit holes; this is how my brain works and often how I’ve noticed my children questioning various ideas or words that pop into their heads as I am trying to teach them something else entirely! While, at times, constant questions can feel irritating (like a distraction or an interruption to what you are trying to teach or accomplish), the rabbit holes are your friends!

If this resonates with you, check out our post on the learning concept behind Five in a Row, Low-Floor, High-Ceiling, which explains in more detail how interest-based learning can allow every student to thrive and take their interest as far as they want to. Click here to read more about Low-Floor, High Ceiling, and Five in a Row.

Rabbit holes are simply questions; they are interest-based opportunities that can lead to gaining knowledge rapidly and retaining information.

The most important reason to allow your child to question and go down a rabbit hole is that you are teaching them how to search for answers to their own questions—you are teaching them how to learn and why we learn!

This will enable them to learn anything and everything they want or need to in school and life.

Are You Considering Homeschooling?

Are You Considering Homeschooling?